The Role of Lactic Acid in the Management of Bacterial Vaginosis: A Systematic Literature Review

Authors: Werner Mendling, Maged Atef El Shazly and Lei Zhang

Abstract

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common infection characterized by an imbalance in the vaginal microbiome. Alongside the extensive research for effective therapies, treatment recommendations for symptomatic BV with antibiotics have been developed and are currently available. However, the recurrence of BV remains a considerable challenge given that about 60% of women experience BV relapse within six months after initial treatment. In addition, clear guidelines on the treatment of asymptomatic BV during pregnancy or for BV mixed infections are still missing. Lactic acid has been put forward as a potential treatment or for prophylaxis of BV due to its ability to restore the imbalance of the vaginal microbiota and to promote the disruption of vaginal pathogenic bacterial biofilms, which might trigger BV recurrence. This review evaluates the clinical evidence regarding the efficacy and prophylactic potential of lactic acid in BV through a systematic literature search. In addition, a treatment regimen consisting of lactic acid as a standalone treatment or in combination with current recommended therapies for practice is suggested based on these findings and stratified according to BV severity, pregnancy status, and coincidence with vulvovaginal candidosis (VVC) or trichomoniasis.

Keywords: bacterial vaginosis; lactic acid; mixed infections; vaginal health

1. Introduction

Over 560 bacterial species have been identified in the vaginal microbiota by genomic sequencing [1,2]. Usually, the healthy vaginal microbiota is dominated by lactobacilli which provide support in the defense against dysbiosis and infections [3–8]. Disruption of the vaginal microbiota balance can result in the development of bacterial vaginosis (BV), a common dysbiosis of the lower genital tract affecting about one third of women of reproductive age in the United States [9–11]. Although the exact cause of BV is still unknown, the disease is defined by a replacement of lactic acid-producing lactobacilli with overgrowth of several strains of anaerobic bacteria [12–15]. Moreover, a critical mixture of BV-associated bacteria in combination with the presence of certain lactobacilli species seems to be implicated in the development of BV and the development of polybacterial biofilms [16,17]. The prevalence of BV varies with race and ethnicity, and occurs more frequently in women that have sex with other women, have a new or higher number of male sex partners, smoke, douche, use hormonal contraceptives, or are subjected to chronic stress [18,19]. As such, BV prevalence in black and Hispanic women within North America is significantly higher (33% and 31%, respectively) compared with white (23%) and Asian (11%) racial groups [20–22]. The economic burden of symptomatic BV is therefore high and has been estimated to cost USD 4.8 billion annually [20].

Up to 50% of women with BV feel asymptomatic, while common symptoms in cases of symptomatic BV include an elevated vaginal pH, grey-white milky vaginal discharge, itching, and a “fishy” odor [23–26]. Aside from the evaluation of clinical symptoms, the gold standard for the confirmation of BV diagnosis is the Nugent score [27,28]. However, traditional assessment using Nugent scoring typically requires more time, resources, and expertise, which can impact its use in a clinical setting [9]. The preferred alternative in practice is the Amsel scoring or a gram stain [23,29,30]. The Amsel scoring system is simple to use and is based on four predefined criteria: (I) the presence of homogeneous, thin, greyish white vaginal discharge, (II) a vaginal pH over 4.5, (III) a positive whiff-amine test, and (IV) >20% clue cells/high power field on a wet mount of vaginal secretions. Yet important diagnostic tools for BV are the phase contrast microscope and a trained user [31,32].

A proper diagnosis of BV is of clinical relevance, since these infections enable the transmission of sexually transmittable infections, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2), and can cause preterm birth and miscarriage in pregnant women [9,33–39]. Over the last decades, several treatments have been developed, and therapy guidelines of BV treatment are now publicly available [40,41]. However, despite these treatment guidelines, recurrence rates of BV remain high, as illustrated by 30% recurrence after 3 months or 60% after 6 months [3,42,43]. The formation of biofilms might be partially responsible for this phenomenon, as recommended antibiotic therapy with oral or vaginal metronidazole or clindamycin are not able to destroy these [3,17,40,44]. The antiseptic dequalinium chloride, which is also recommended in the World Health Organization/International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections (WHO/IUSTI) guideline, can dissolve BV-associated Gardnerella biofilms only in vitro [41,45]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that treatment with metronidazole does not result in restoration of the healthy vaginal microbiota [46]. Therefore, additional therapies and prophylactic treatments after initial therapy, such as probiotics, pH-regulating products, and vaginal or oral lactobacilli, are desired to control maintenance of the healthy vaginal microbiota [47–54].

Among these additional therapies, lactic acid has been put forward as a potential candidate for the prophylaxis and treatment of BV [55]. Lactic acid, in combination with hydrogen peroxide, bacteriocins, antiadhesive molecules, and cytokines, is mainly produced by lactobacilli in the healthy vagina and protects the vaginal microbiota against BV-associated bacterial strains [56–59]. In addition, lactic acid has virucidal properties and is able to kill C. trachomatis [60–63].

In this review article, the efficacy and prophylactic potential of lactic acid as a standalone treatment or in combination with antibiotics as a therapy for BV is systematically reviewed. In addition, recommendations for BV treatment according to specific patient groups, stratifying between first-time BV, recurrent BV, pregnant with BV, planning pregnancy, or in mixed BV infections, have been proposed. There is a specific focus on mixed infections, since no recommendations are available for this patient population.

2. Methods

An electronic, systematic literature review was conducted by consulting the PubMed and Cochrane Library databases from inception until 7 May 2021 by 1 reviewer, and was independently verified by the authors. Various combinations of terms were queried, including “bacterial vaginosis”, “non-specific vaginitis”, “vaginal bacteriosis”, “mixed infections”, “lactic acid”, and “lactate gel”. Articles were considered eligible if they assessed vaginal lactic acid-containing products as a standalone treatment for BV or in combination with antibiotics, preferably in comparison to placebo or standard of care. Inclusion of articles in the current review were restricted to clinical trials that studied the efficacy of lactic acid in BV. Study populations with first time and recurrent BV, as well as pregnant study populations, were included in the review. Only English-written articles were considered. Additionally, relevant references cited in the primary studies were tracked. There were no size or date restrictions. Studies were excluded if they were performed on animals or if they included treatment with lactic acid producing bacteria. Unpublished studies, reviews, and case studies were not reviewed.

3. Results

In total, 213 results were retrieved from the literature search, of which 51 abstracts fulfilled the predefined inclusion criteria and were further evaluated. Based on the abstracts, 12 full text articles were then reviewed for eligibility, of which 7 fulfilled the predefined criteria to assess the efficacy of lactic acid in the prophylaxis and treatment of BV. Figure 1 depicts a PRISMA flow diagram describing the literature search and article selection process. The main reasons for article exclusion after fulfillment of the inclusion criteria were endpoints not being related to efficacy of lactic acid [64], involvement of treatment with Lactobacillus spp. as a means to increase vaginal lactic acid concentration [65], or focus on changes in the vaginal microbiota [66,67], which are beyond the scope of the current review. One study would have qualified to be included in this assessment but was still in progress with no efficacy results published at the time the literature search was performed [29].

Of the seven selected clinical study publications, five evaluations studied the effect of lactic acid in symptomatic BV in comparison to the recommended treatment with antibiotics (Table 1). One study focused on treatment of recurrent BV, and one evaluated the use of lactic acid in symptomatic pregnant women. All but the final study was designed as randomized controlled trials.

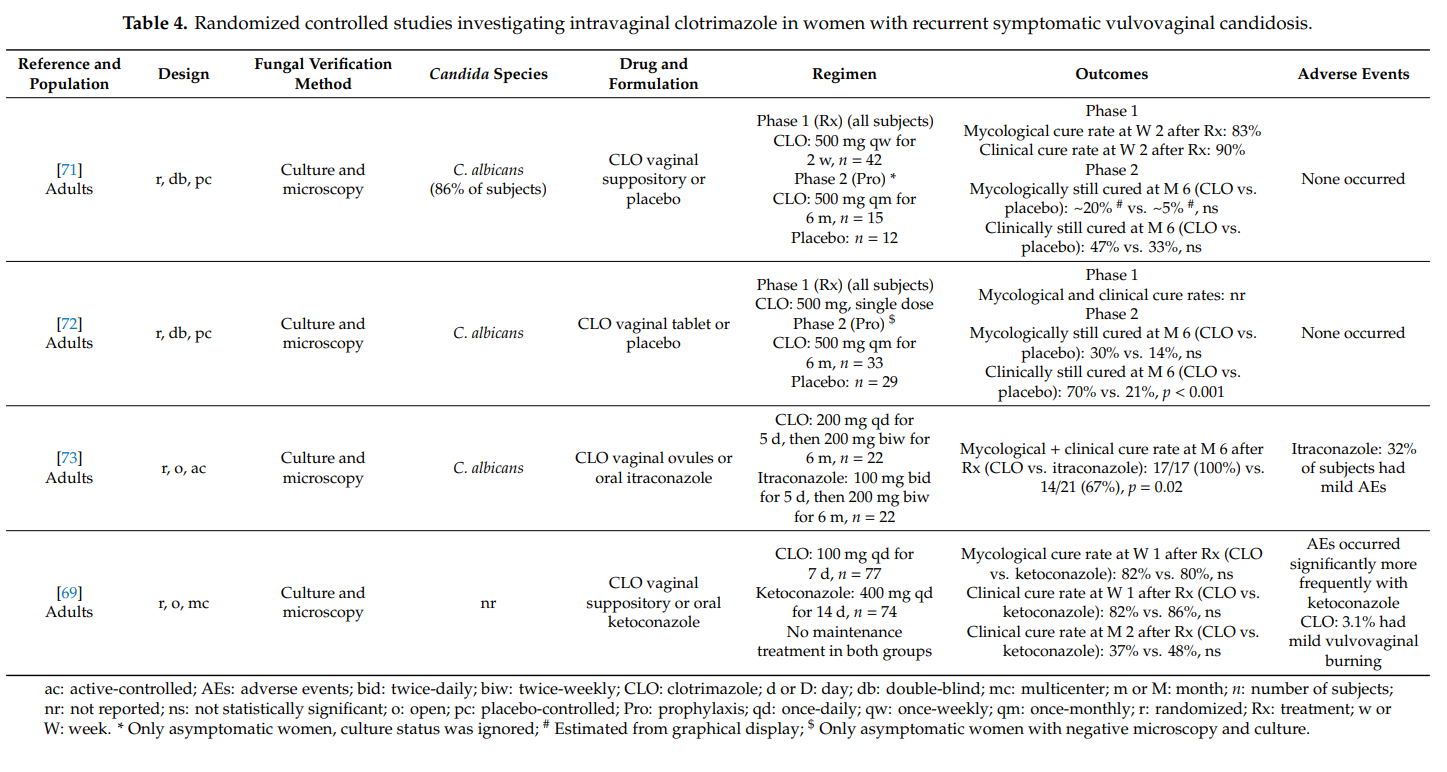

3.2.2. Recurrent Vaginal Yeast Infection

Recurrent symptomatic vaginal yeast infections may have a severe adverse impact on the quality of life. Defined as ≥4 culture-proven episodes per year, it is a long-term condition causing significant morbidity in women [68]. The highest prevalence (9%) has been observed in young women aged 25–34 years [8]. The main fungal species causing recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis is still Candida albicans. In fact, in about 85–95% of cases, azole-sensitive Candida albicans can be identified as the responsible pathogen. The latter implies that peculiarities of the host (e.g., genetic factors that facilitate vaginal colonization and persistence) must contribute to the development of disease recurrence [68]. Optimized treatment regimens are required to combat this debilitating and complex disease. Usually, an induction course followed by maintenance or intermittent treatment for at least 6 months is pursued [14].

We found four randomized controlled studies investigating intravaginal clotrimazole in non-pregnant women with recurrent symptomatic vulvovaginal candidosis (Table 4). Clotrimazole induction treatment for 1–2 weeks (e.g., clotrimazole 100 mg once-daily) resulted in short-term mycological and clinical cure rates of >80%. Intermittent once-monthly prophylactic administration of clotrimazole 500 mg (solid system) for 6 months prevented clinical disease recurrence in up to 70% of women, but did not prevent vaginal recolonization with Candida albicans in the majority of cases. More subjects on intermittent intravaginal clotrimazole remained asymptomatic than subjects receiving intermittent oral itraconazole or placebo. In one head-to-head study, clotrimazole and oral ketoconazole induction treatments were equally effective at achieving high short-term cure rates, but without immediate initiation of maintenance/intermittent therapy, longer-term recurrence rates were high in both groups [69]. Except for occasional vulvovaginal burning, topical clotrimazole was well tolerated in all four studies. Adverse events were significantly more common with oral itraconazole and oral ketoconazole than with intravaginal clotrimazole.

Our findings summarized in Table 4 must be put into perspective with the fact that higher cure rates have been reported with oral fluconazole. In a randomized controlled study in 387 women with recurrent symptomatic vulvovaginal candidosis, oral fluconazole 150 mg was administered on days 0, 3, 6, followed by once-weekly intakes for 6 months. The proportion of women who remained clinically cured until 6 months was 91% in the fluconazole group and 36% in the placebo group (p < 0.001). During the maintenance phase, 2.9% of patients in the fluconazole group and 1.2% in the placebo group reported at least one adverse event that led to discontinuation of the study medication [70].

3.2.3. Severe Vaginal Yeast Infection

Severe vulvovaginal candidosis is characterized by extensive vulvar erythema, swelling, excoriation, itching and fissure formation. Standard treatments as used in uncomplicated vulvovaginal candidosis are insufficient in women with severe disease; intensified treatment regimens comprising repeated doses are required [4,10,14].

We identified one article qualifying for inclusion in our review. Zhou et al. [74] conducted a prospective, open, randomized (1:1) study in 240 women with severe vulvovaginal candidosis to assess whether two 500 mg doses of clotrimazole vaginal tablet are as effective as two 150 mg doses of oral fluconazole. In each group, the two doses were administered 3 days apart. Study participants were to be not pregnant and at least 18 years old. In 90% of cases, Candida albicans was the causative pathogen. The mycological cure rates at days 7–14 after therapy were 78% and 74% (p = 0.147) in the

clotrimazole group and the fluconazole group, respectively. The corresponding clinical cure rate was 89% in both groups. At days 30–35, the mycological cure rates amounted to 54% and 56% (p = 0.813) in the clotrimazole group and the fluconazole group, respectively; the clinical cure rates at that time point were 72% and 78% (p = 0.298), respectively. Systemic adverse events were more common with oral fluconazole (e.g., headache) than with intravaginal clotrimazole, while local adverse events (e.g., mild burning) occurred more frequently in the clotrimazole group. It was concluded that the two tested treatment regimens are equally effective, with a safety benefit for clotrimazole.

3.1. Clinical Evaluation of Lactic Acid in Symptomatic BV

The potential of vaginally applied lactic acid to treat BV has been studied since 1986. In one study, Andersch et al. randomized 104 women with BV who received either one nightly intervaginal dose of lactate gel or a comparator treatment with 500 mg oral metronidazole twice daily for 7 days [74]. One week after treatment initiation, lactate gel demonstrated equal efficacy in comparison to treatment with metronidazole as demonstrated by an Amsel score of ≤2 out of 3. No adverse events were reported.

Another study compared the efficacy of intravaginal lactic acid with oral metronidazole (500 mg, twice daily, 7 days) and a placebo-treated group at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 3 months after treatment initiation [68]. Two weeks after treatment, 49% of the lactic acid-treated study group presented an Amsel scoring ≤2, in comparison to 83% of the metronidazole and 47% of the placebo-treated group. The median duration for curative results was 21 days in the comparator metronidazole-treated population, where complete disappearance of symptoms occurred in 50% with the lactic acid up to 90 days after treatment initiation. The authors reported no difference in adverse events between the three treatment groups.

Treatment of BV with 5 g of lactic acid vaginal gel at bedtime for 7 days, alone or in combination with 500 g oral metronidazole twice daily for 7 days, resulted in a significant increase in Lactobacillus spp. colony count after 2 weeks in comparison with metronidazole alone [69]. The clinical efficacy, as assessed by a decrease in vaginal pH, clue cells, and whiff test, was similarly efficient for the three treatment groups. Analysis of adverse events showed that women treated with metronidazole experienced minimal side effects, which were absent with lactic acid treatment.

Sustained-release oligomeric lactic acid pessary, in comparison with an untreated control group, has also been evaluated [70]. The study consisted of two parts: a two[1]week proof-of-concept evaluation and a one-week efficacy evaluation. The pessary was administered once or twice per week and showed an overall efficacy of 78% BV clearance after 1 week. Reported adverse events were mild and short-term.

In a randomized clinical trial, women with symptomatic BV as diagnosed by Amsel criteria and Nugent score, were evaluated [71]. Subjects were either allocated to receive treatment with daily Acidform gel or metronidazole intravaginal gel for five days. Approximately one-week post-treatment, 23% of women who received Acidform and 88% of women treated with metronidazole were cured. According to Amsel criteria, 28 to 35 days after treatment initiation, the percentage of women cured decreased to 8% in the Acidform group and to 53% in the metronidazole-treated group. Four women receiving Acidform and one woman receiving metronidazole reported genital irritation.

3.2. Clinical Evaluation of Lactic Acid in Recurrent BV

Follow-up clinical evaluation was used to determine how the intermittent prophylactic use of vaginal lactate gel after initial treatment with lactic acid-containing gel resulted in 88% of BV symptom relief 6 months after treatment initiation [72]. This was significantly higher than the placebo-treated group, where only 10% of the population presented clinical improvement of BV symptoms. Although this was the only study with a specific focus on BV recurrences, it also reported long-term BV outcomes after initial treatment [68,71]. Recurrence rates of BV after metronidazole and lactic acid treatment were similar in comparison to the placebo-treated group at 3 months after treatment initiation [68]. In contrast, in comparison with intravaginal metronidazole treatment, a lower BV recurrence rate 1 month after lactic acid treatment was observed [71].

3.3. Clinical Evaluation of Lactic Acid in Symptomatic BV during Pregnancy

A positive change in the vaginal microbiota has been demonstrated starting from 2 days after treatment initiation with lactic acid in pregnant women with symptomatic BV [73]. After 1 week, 80% of the treated women were declared cured with the presence of a normal concentration of lactobacilli in the vaginal microbiota.

4. Discussion

Although local lactic acid has been demonstrated to exert beneficial effects through its capacity to destruct vaginal biofilms and restore vaginal microbiota in BV without causing systemic effects, use of lactic acid in the prophylaxis or treatment of BV is currently not included in treatment guidelines. Therefore, this review provides a summary of the current BV treatment guidelines and proposes additional treatment regimens based on clinical findings and according to predefined patient groups, differentiating between pregnancy status, BV recurrence rates, and presence of additional pathogens. In addition, the authors propose to not only determine the treatment on Amsel criteria, but also on Nugent scores or modern microbiome diagnostics.

4.1. BV in Nonpregnancy

4.1.1. First Time BV

To date, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexually Transmitted Disease Treatment Guidelines recommend all symptomatic women with BV to be treated with antibiotics primarily to relieve vaginal symptoms and signs of infection [29]. The recommended treatment for symptomatic BV consists of oral metronidazole (500 mg, twice daily, 7 days or 2 g, 1–2 times per day in 48 h), vaginal metronidazole (500 g, 1–2 times, 7 days or once 2 g), clindamycin vaginal cream (2%, 7 days), or vaginal dequalinium chloride (10 mg, 6 days) [75]. It should be noted that over half of women with BV are reported to be asymptomatic, causing the debate as to whether or not treatment of this specific population should continue [8]. The main argument to treat asymptomatic BV might be because of its sexually transmittable characteristics and increased risks of postoperative infections or complications after gynaecological interventions, regardless of absence of symptoms [76–79].

Five clinical studies identified in the current systematic literature review evaluated the efficacy of lactic acid as a treatment of symptomatic BV. Lactic acid treatment resulted in similar cure rates when compared to metronidazole treatment [69,74], and the use of a pessary containing lactic acid was effective against BV in comparison to a placebo-treated group [70]. However, no increased cure rates were reported when patients were treated with lactic acid as compared to placebo, in contrast to metronidazole treatment, which showed a significantly higher cure rate [68,71].

The observation that the retrieved clinical studies do not reach a clear consensus on the use of lactic acid as a treatment and prophylaxis of BV might indicate that an alternative patient population stratification is desired. As such, a differentiation between patients with mild BV, here defined as developing BV with a pH value of 4.5 or 4.6 and microscopic presence of only few clue cells, and moderate to severe BV, characterized by a pH value ≥4.7 and abundance of clue cells, is proposed. Based on assessment of the available information, it is the authors’ proposal that subjects with mild BV could benefit from treatment with lactic acid alone through restoration of lactobacilli colonization and prevention or destruction of biofilm formation (Table 2) [56–58,80,81]. The use of lactic acid alone could provide required efficacy in this population, while avoiding systemic effects, side effects, and bacterial resistance associated with antibiotic use. As has been established, BV cannot be cured with lactic acid alone; however, the combination of currently recommended therapy with antibiotics and lactic acid should provide efficacious BV symptom relief and stimulate lactobacilli recolonization of the vaginal microbiota [68,69,71].

4.1.2. Recurrent BV

To date, recurrence rates of BV within a few months after initial treatment remain high [3,14,42,82,83]. The formation of biofilms, presence of residual infection, resistance because of poor treatment adherence, reinfection through intercourse, or the failure to restore protective vaginal lactobacilli populations have been identified as potential causative factors [17,84,85]. According to the current guidelines, recurrent BV is usually targeted through long-term weekly use of vaginal metronidazole for 4 to 6 months or by repeated cycles of oral metronidazole or tinidazole for 7 days upon BV recurrence.

Previous observations have shown that prophylactic use of lactic acid after initial BV treatment results in significant clinical improvement after 6 months in contrast to placebo treatment, with lower rates of BV recurrence [71,72]. Of note, although it is generally perceived that antibiotic therapy efficiently treats BV and prevents recurrences for a longer period of time, the use of lactic acid gel is preferred by patients as prophylactic treatment or in mild BV cases [29]. This is likely mainly due to the ease of use, lower frequency, and fewer side-effects for lactic acid therapy.

Treatment of recurrent BV with lactic acid in addition to the recommended guidelines with antibiotics is advised to promote prevention of BV recurrence and reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance (Table 2) [10,69,71].

4.2. BV in Pregnancy

The prevalence of BV in pregnant women varies significantly according to region, and is estimated to be 14% in a Canadian study [21,22,86–88]. The diagnosis of BV during pregnancy is clinically significant because of its association with several complications including preterm labor and delivery, late miscarriage, and postdelivery infections [89–97]. In addition, presence of sexually transmittable diseases, which can be increased through presence of BV, is also correlated with preterm delivery if it remains untreated [98,99].

4.2.1. Pregnant with BV

Oral BV treatment with antibiotics has not been associated with adverse foetal or obstetrical effects and is therefore recommended in pregnant women with symptomatic disease [93,100]. The CDC-recommended treatments include oral metronidazole (500 mg, twice daily, 7 days or 250 mg, 3 times per day, 7 days) or clindamycin (300 mg, twice daily, 7 days). In addition, the use of metronidazole for BV in this patient population should be only initiated if alternative treatment is inadequate [9].

As with BV in nonpregnancy, BV can also present asymptomatically in pregnant women. To date, controversy exists about whether treatment of asymptomatic BV during pregnancy decreases the risk for preterm delivery, maternal infections, and miscarriage despite its well-defined association with such risks [101–103]. However, recently published data suggest that treatment of BV should be carried out as soon as possible in early pregnancy, and preferably even before conception, since this would be more efficient in the prevention of preterm birth than treating BV which has become established during pregnancy [104].

Treatment of BV during pregnancy with lactic acid showed a positive change in the vaginal microbiota by restoring normal lactobacilli levels and vaginal acidity [73]. These findings promote the use of lactic acid as an additional therapy for BV during pregnancy on top of the recommended therapy with antibiotics, especially since risk factors for preterm delivery can be defined upfront, including race, ethnicity, an interpregnancy interval lower than 6 months, previous preterm births, age of the mother, and the nutritional status [105]. Despite remaining a topic of debate, it is proposed to also include pregnant women with asymptomatic BV and a high risk of preterm birth into the combined treatment group with antibiotics and lactic acid in order to avoid complications for the mother and foetus (Table 2).

4.2.2. Planning Pregnancy with Mild BV

To date, it is not current in practice to screen for BV in women planning pregnancy, and there are no recommendations for this patient group [106]. However, awareness of BV remains a crucial element in order to prevent potential BV complications during pregnancy. Therefore, given the beneficial effects of lactic acid, low associated risks, minimal side effects, high acceptance, and ease of use, treatment with lactic acid should be promoted in this population in case BV is suspected (Table 2).

4.3. Mixed Infections

In rare cases, BV can also coincide with vulvovaginal candidosis (VVC) or trichomoniasis, resulting in mixed vaginitis, a condition where both pathogens contribute to an abnormal vaginal milieu [107–109]. VVC is one of the most frequent vulvovaginal infections worldwide caused by the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans [110]. It is estimated that 70–75% of women experience VVC at least once in their lifetime and 40–50% will suffer from repeated episodes during their lifetime [111–113]. Coincidence of BV with VVC occurs in about 5% of vaginitis cases and is difficult to diagnose since a differentiation needs to be made between colonisation and infection by C. albicans [107,114,115]. In addition, clinical symptoms of BV and VVC can be similar, requiring a well-trained microscopic investigation together with a good anamnesis and clinical experience to accurately determine the diagnosis.

Trichomoniasis is caused by Trichomonas vaginalis and is the most prevalent nonviral sexually transmitted disease worldwide. Its prevalence varies geographically, ranging from 5.8% of all women in Europe to 20% and 22% in Africa and the Americas, respectively [116]. Mixed infections of BV and trichomoniasis are very rare, as illustrated by incidence rates of 0.8% in a general emergency department population [117]. However, in African American pregnant women, the incidence of BV together with trichomoniasis can reach 15% [118].

The diagnosis of a mixed infection is crucial in the treatment of the disease to initiate appropriate therapy, especially since the United States Food and Drug Administration does not permit drug combinations for the treatment of mixed infections in order to encourage physicians to reach a correct diagnosis and to treat precisely according to medical and ethical principles [107]. Since no guidelines are available for the treatment of mixed infections, the physician should consider from which of the two conditions the patient suffers the most and initiate treatment based on that. For example, patients will typically suffer more from symptoms associated with VVC, as often characterized by itching and soreness in the vestibulum, and trichomoniasis compared with BV-associated symptoms, such as fishy odor without signs of infection [110].

In case of mixed infections of BV with VVC or trichomoniasis, it is encouraged to focus first on the treatment of VVC with antimycotic treatments or on therapy against trichomoniasis by a single dose of oral metronidazole or tinidazole (Table 2). In the latter case, the antibiotic treatment will also affect BV. If symptoms persist, treatment of BV should be the secondary goal according to the treatment recommendations and stratified to BV severity and pregnancy status, and the combination of lactic acid as a standalone or in combination with antibiotic therapy should also be encouraged. It should also be emphasized that lactic acid has been demonstrated to have beneficial effects against VVC and trichomoniasis [35,65,119–121]. In case of VVC, this effect can be due to the increased solubility of clotrimazole and a higher sensibility of the pseudohyphae of C. albicans against clotrimazole due to their activated metabolisms in contrast to budding cells in the presence of lactic acid [122]. These arguments led to the combination of clotrimazole 500 mg vaginal tablets with lactic acid [122]. In addition, a recent study showed that Chinese women with mixed infections had a significantly higher abundance of Mycoplasma, Prevotella, Streptococcus, Anaerococcus, Dialister, Peptostreptococcus, and Peptinophilus, while presenting with a significantly lower concentration of Lactobacillus spp. than with trichomoniasis alone [123]. The authors conclude that probiotic pessaries could provide a solution for the shift towards a balanced vaginal microbiome, implying that lactic acid, the physiological product of lactobacilli, could also be a good choice to help to restore the abnormal microbiome in mixed infections.

5. Study Limitation

The limitations of the approach and results of the review will now be discussed. As mentioned above, the articles included for assessment here were selected from a search of PubMed and the Cochrane Library database from inception until 7 May 2021 by one reviewer. This was restricted by the length of time available for the research and the databases accessible at the time and as a result, it has unfortunately not been possible to include some of the more recently published articles on the topic in the full discussion [124,125]. However, one study which was underway when the present paper was being researched is now completed [29,125]. In [125], it was reported that participants with recur[1]rent BV had a higher response to treatment with metronidazole than with lactic acid gel at 14 days, but subsequent recurrence of symptoms over 6 months was common in both arms. While metronidazole was more likely to be cost-effective compared with lactic acid gel, participants interviewed in a qualitative sub-study disliked taking a repeated course of antibiotics for BV, preferring the lactic acid gel, even if its short-term efficacy was lower than metronidazole, supporting the potential use of lactic gels for BV treatment for some subjects.

The results published regarding the efficacy of lactic acid in the treatment and pro[1]phylaxis of BV does not always reach a clear consensus in a clinical setting and are limited. The variation in efficacy results might be partly due to generalization of the study population, despite different grades of BV severity, and the administration route. More randomized, controlled, adequately powered clinical studies are required to further evaluate the effect of lactic acid in BV [126]. However, the protective and potential curative effects of lactic acid in BV have been extensively explored and are demonstrated to be of added value [56–58,60,61].

The work presented here has focused on BV, and it has not been possible to go into aerobic vaginitis in depth in this report. The authors hope to revisit this topic, if possible, in the future.

6. Conclusions

BV remains a widespread and often recurrent condition impacting the health and quality of life of its subject. Although traditional treatments for BV have been extensively explored, therapy recommendations are widely available, and initial treatment with antibiotics is very effective, the prevention of high BV recurrence rates remain an important challenge, especially because of the considerable impact of BV on patients’ quality of life [17]. Based on the available literature, recommendations have been made regarding the concomitant usage of lactic acid-based treatments with current BV treatment regimens. These could provide added value by stimulating restoration of the healthy vaginal microbiota and disrupting pathogenic biofilms, thereby aiding in the treatment of BV and prevention of recurrent infections. Fact-based guidance is important for building trust with the patient. Discussion about the use of lactic acid gel for BV treatment with the patient should include information about its potentially lower short-term efficacy compared with traditional antibiotic therapy, but balanced with information about reduced side effects and similar rates of recurrence in addition to removing the need for antibiotic usage.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the writing, review, and editing of this article. W.M. provided substantial contributions to the conception of this work and the interpretation of study data. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: The work was funded by Bayer Consumer Care AG, Basel, Switzerland. Writing assistance was provided by Leni Vandekerckhove (MediGraphX, Belgium) and Jonathan Crowther (JMC Scientific Consulting Ltd., United Kingdom) who were funded by Bayer Consumer Care Ag, Basel, Switzerland.

Conflicts of Interest: W.M. has received honoraria for oral presentations at scientific congresses or meetings of experts. M.A.E.S. and L.Z. are employees of Bayer Consumer Care AG, Basel, Switzerland.